Is Maya a living language?

Many people don’t realize that the Maya language is still very much alive; they feel it is just hieroglyphs carved on cave walls and on stone stelas, disappeared with the ancient communities like Chichén Itzá and Tulum. The Maya language is very much alive and there are 32 Mayan languages derived from Yucatec Maya and these are spoken by over 5 million people from the Yucatan Peninsula to Chiapas, and down through Belize, Guatemala and Honduras.

In Quintana Roo and throughout the Yucatan Peninsula, approximately 700,000 people still speak Maya. It is referred to as ‘Yucatec’ Maya to foreigners, or just ‘Maya’ to locals. Other dialects such as Tzotzil Maya and Tzeltal Maya, which are spoken in Chiapas, or K’iche' Maya which is spoken in Guatemala, are usually referred to by their specific name rather than being called ‘Maya’ like in the Yucatan Peninsula.

As Maya is mostly an oral language, there still isn’t one standard for its spelling. International Maya language scholars have been trying to set a standard for the spelling of Yucatec Maya for several decades. However, sounds can differ in very minor ways from one region of the peninsula to another, so a single standard is still being debated. Most Maya speakers do not know how to write it but there is a current push in the local academic community to teach young students in bilingual (Maya/Spanish) primary schools in the Maya communities to learn how to write in Maya, as well as in Spanish. In addition, bills are getting brought to the Mexican Federal Congress to put more funding into the preservation and teaching of indigenous languages. The state government of Quintana Roo accepted the state’s anthem translated into Maya and local students are now learning it in schools. Laws and rights are also getting published in Maya, but community leaders say the government needs to do more to include the Maya language in schools and government entities.

Maya basics, Yucatec Maya’s tones and glottal stops

Although Maya is spoken in Mexico where Spanish is the national language, Maya has no relationship to Latin-based languages like Spanish. It does have its own highly-structured grammar of pronouns, verbs, adjectives and tenses. One of the most intriguing parts of Yucatec Maya is how it sounds. It has hard, quick k’, ch’, p’, t’, ts’ consonant sounds, formally known as glottalized stops, which don’t exist in the same way in Spanish or English. Here’s a Maya language student explaining how the hard k’ can be pronounced.

It also has five different sounds for each vowel which are defined by the tone and length of the pronunciation of the vowel. In modern-day written Maya, these sounds are defined with accent marks, apostrophes and by doubling up the vowel. It’s considered a tonal language with a high tone usually marked with an accent on the vowel. For example, the ‘a’ with an accent: á, in the word k’áan’, the voice rises on the first accented vowel and drops for the second vowel.

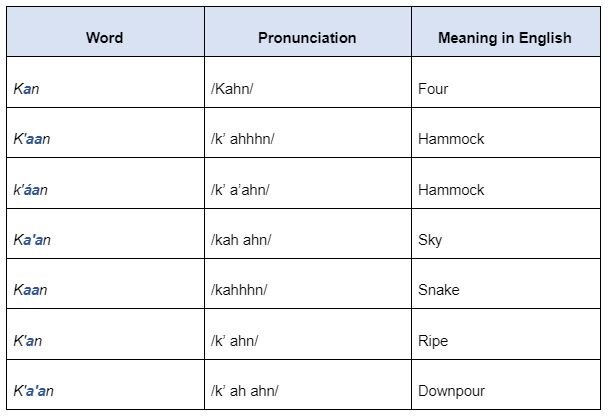

The low tones are usually marked by a double vowel. For example, the word kaan has a double ‘a’. The voice drops while saying a dragged out sound like ‘ahh’ with the voice falling in tone. In some cases, each different tone, vowel and consonant glottal stop and vowel combination has a different meaning. Let’s take the word, kan /kahn/, in Maya. There are seven different ways to pronounce the ‘a’s and/or ‘k’ and each word has its own meaning:

In addition to these glottal stops and vowel combinations, there are different voices for verbs in Yucatec Maya where the verb combinations change the tense of the same verb. The vowels are classified as simple, long-tone low, long-tone high, rearticulated and glottal in the different voices or tenses of the language. There are vowels that are considered ‘active’ (a, e, i, o, u), passive (a’a, e’e, I’I, o’o, u’u), antipassive (aa, ee, ii, oo, uu) and medium (áa, ée, íi, óo, úu). We’ll look at the example of the verb ch’aak meaning ‘to cut’.

In this example, there are morphological elements that indicate the changes in the tone and these clearly distinguish each voice through the accents and apostrophes.

The intonation of Yucatec Maya

Another fun part of the Maya language is its sing-song intonation. When a Spanish word slips into a conversation in Maya, the intonation stays. For example, modern-day Maya speakers don’t have translations for the words presidente (president) or lunes (Monday) but when they’re pronounced by a Maya speaker, they sound sing-song-y: low-high-low-high /pres-ee-den-té/ or low-high /loon-és/ with the last syllable usually ending on a high tone no matter how many syllables the Spanish word has.Once a Yucatec Maya language learner understands and recognizes these tones and glottal stops when listening to Maya speakers, the language becomes a bit more understandable. It can even make it fun when those untranslated Spanish verbs get slipped into conversations. Many visitors to the region feel that Spanish is spoken more slowly and is easier to understand than other parts of Mexico. This is true as many speak Spanish as a second language to Maya or learned from parents and grandparents who spoke Spanish as a second language.

Credits: Paulino Eleazar Ek Martin, Na'atik Maya and Spanish teacher

If you want to see a real-life example of Maya being used by one of our Maya students when he came to visit the region, check out the video below:

If you would like to read more about Mexican culture, history, cuisine and language, check out our blog page for our latest monthly articles. You can also sign up to our newsletter to receive these straight to your inbox along with the latest news about our non-profit school for local and Indigenous students in Felipe Carrillo Puerto.

The best way to experience the Mexican lifestyle is in person, with a Na’atik Immersion experience. Not only do you live with a local Mexican-Maya family, sharing home-cooked meals and free time, but also receive expert instruction in your chosen language at our school. Best of all, every immersion experience helps fund our subsidized and free local education program, helping local students to access opportunities and make their own futures.